The question that is always asked is “How can such crimes take place in and around local authorities and law enforcement agencies?” Most of the workers, in the order of thousands, are not Cambodians, but yet they have managed to get in to Cambodia, or been smuggled-in, without normal immigration and work permission formalities.

Even more surprising to outsiders, but not those of us who have lived and worked in Cambodia, is how such trafficking of people evades the local authorities. The ruling party openly boasts about its

vast network

down to sub-village levels. The lowest representatives, serving the party, are invariably also assistant village chiefs. In fact most can't distinguish their duties for the party from their official public service administrative roles. Let us be clear. They do not miss anything that goes on in their allotted areas. There are approximately 1,652 communes in Cambodia and 14,750 villages. Each has a village chief and several assistant village chiefs.

In November 2017, Cambodia's Supreme Court, doing the ruling party's bidding, legally banned the Opposition Party CNRP. Within hours every CNRP outpost, even in the most remote places, were visited and their sign-posts dismantled.

It proves that there is no way that any of these scams go on without blessing from upon high and that nearby local authorities, police, and courts must not interfere.

Finally I wish to make a relevant observation. There are basically

two approaches to the work of countering human rights abuses. One is “constructive engagement” with authorities where donors and NGOs work directly with police and judicial authorities. The other is where NGOs keep their distance from authorities, so as not to be compromised or co-opted, and seek to elicit change externally through a variety of means. Often advocacy is tried first but when it is to no avail what amounts to

“Name, Blame, Shame” is their only potentially effective resort.

My organisations and projects have tried both approaches over the years in Cambodia. Sadly neither approach has proven to work in the face of intransigent authorities. Constructive engagement in our human rights and good governance efforts led to no discernible change in public service processes or standards. There used to be more success with

“Name, Shame, Blame” especially if you warned authorities beforehand for them to act first, but this has all but disappeared increasingly since 2011. That was when the Cambodia Government ended its regular sessions with donors as a group to monitor progress on reforms. It also marked the crackdown on all forms of #CivilSociety, closing organisations down or co-opting them. The process then accelerated after the 2013 elections, after Prime Minister

was

shocked by the results.

"After the 2013 national elections, the ruling party was given a real shock – the opposition was close to winning, and perhaps would have done if the elections had been conducted fully freely and fairly. Soon after, still in shock, a very contrite subdued Prime Minister gave a 5 hour speech to his ministers and the country to “scrub themselves clean”.

Astute as ever, he soon realized that to take on his friends was much harder (and more dangerous) than his enemies, and so he set about “detecting, disrupting, and destroying” all forms of opposition, whether party political, or neutral civil society, anywhere where absolute loyalty could not be assured."

Strangely most donors have

reacted mildly to the crackdowns or not at all to such, reneging on their international guarantees.

Conclusion

What “Human Trafficking” Foreign Aid interventions demonstrate abundantly is direct “constructive engagement” via bilateral aid with the Cambodia Government is largely a waste of money. Surely that money could and should be better used to prevent people falling prey to criminals through education, advocacy and direct support to most vulnerable groups.

Updates to this article can be seen on

my blog of the same name.

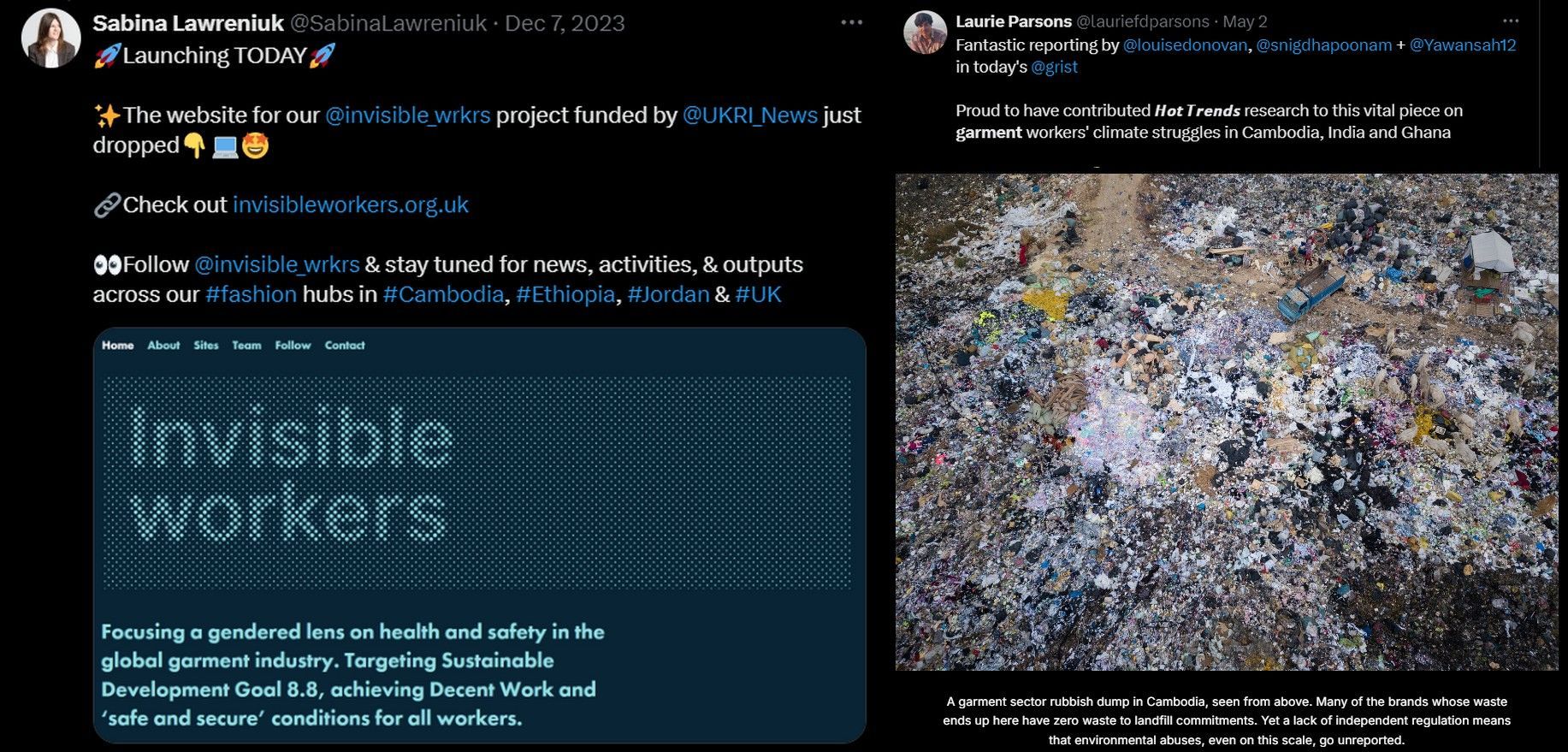

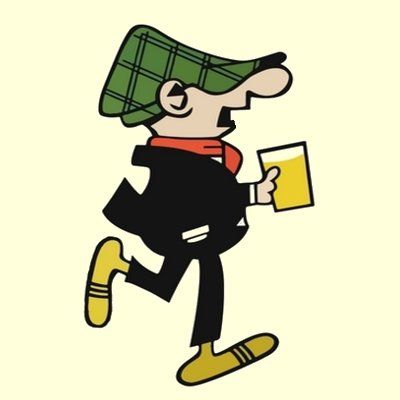

The Garment Girls – Victims of Trafficking or Lucky Employees?

Cambodia has become a major player in the production of garments, footwear, and other mass-produced items. Indeed they are the nation's main source of revenue.

These industries employ large numbers of workers. Most are young women from poor households with few other work opportunities for them, obliged to provide extra income for their families, meaning that the demand for such jobs far exceeds availability. This helps to explain why employers are able to avoid giving better pay and conditions while resisting collective bargaining efforts of trade unions. In general the government sides with employers.

The question is

“Are these young women exploited?”

The answer to that is a clear

“Yes!”

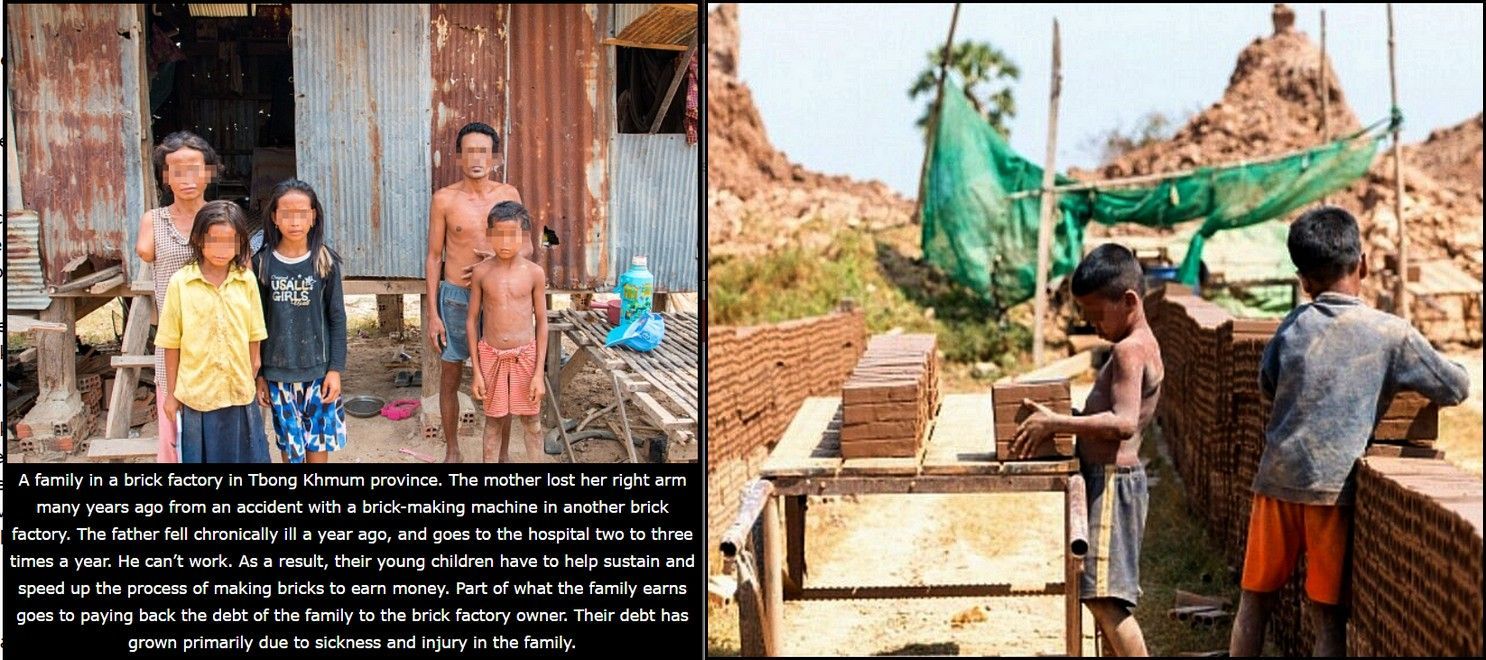

Exploitation

actually starts in their home. Poor families do pressure children to help family budgets. The eldest child especially if a girl is expected to

make sacrifices for her family. Therefore very many are pressured to leave home to go in search of paid work. Then once obtained – in whatever job either “above board” like sewing garments or dubious ones like hospitality – they are under strong pressure to repatriate as much of the money to their families and skimp on their living expenses. For “dubious” read socially-condemned occupations. Many hide how they make their money. People do look down on these occupations, hence why it is deemed lucky to obtain “respectable” garment jobs.